New research is finding ways to help people overcome poverty and avoid the mental and physical health problems associated with low socioeconomic status.

By Rebecca A. Clay

July/August 2015, Vol 46, No. 7

Print version: page 77

Clay, R. A. (2015, July 1). Fighting poverty. Monitor on Psychology, 46(7). https://www.apa.org/monitor/2015/07-08/cover-poverty

Psychologist Rosario Ceballo, PhD, grew up poor.

Her parents, both immigrants from the Dominican Republic, worked in factories in New York City. One day when Ceballo was a girl, her mother took her to the factory where the mother sewed bathing suits in a vast room filled with row after row of sewing machines. "The family story is that the foreman said, ‘There's a sewing machine waiting for you,' meaning me," says Ceballo. "My mother said, ‘No, she's not going to do this.'"

Ceballo's mother was right. Ceballo's grandmother, a housekeeper who worked for teachers at a private school in New York City, helped Ceballo get a scholarship to that school for 12 years. Today, Ceballo is a professor of psychology and women's studies at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and studies the factors that helped her — and other children — move into the middle class.

Ceballo is one of many psychologists who are conducting research on ways to help people escape poverty. With 44 percent of American children now living in low-income families, according to the National Center for Children in Poverty, these psychologists are investigating how poverty affects the brain and children's ability to take advantage of educational opportunities. They're also exploring how the stress of poverty can lead to heart disease and other life-shortening illnesses. And they're studying what parents can do to help lift their children out of poverty.

Poor children's brains look different from those of their better-off counterparts, according to psychologist Martha J. Farah, PhD, who directs the University of Pennsylvania's Center for Neuroscience & Society.

Using structural magnetic resonance imaging, Farah and her colleagues have assessed the relationship between socioeconomic status and brain development. In a 2013 study in Developmental Science, they examined socioeconomic status's impact on the prefrontal cortex. This region of the brain, the researchers explain, is essential for executive function and thus associated with intelligence and academic success. The prefrontal cortex also has a long developmental trajectory and is sensitive to environmental factors, such as stress. In the study, Farah and her colleagues found that parental education — a common measure of childhood socioeconomic status — significantly predicted the thickness of the prefrontal cortex in children's brains.

Although brain differences may suggest that genetic causes are at work, environmental differences between lower and higher socioeconomic status childhoods are also likely to contribute to the effects we see, says Farah. These include stress, lack of cognitive stimulation, poor nutrition, exposure to lead and other neurotoxins and differences in medical care.

Those brain differences are reflected in children's working memory, problem-solving and other executive function skills, says Farah. Researchers have long known that childhood socioeconomic status predicts executive function abilities, she says. What they haven't known is whether those disparities change throughout childhood, perhaps with accumulating stressors widening the gap or further development and education allowing poor children to catch up.

In a 2015 paper in Developmental Science, Farah and colleagues examined the relationship between socioeconomic status and executive function in data on more than 1,000 children followed longitudinally in a National Institute of Child Health and Human Development study and found that the relationship stayed constant into middle childhood. Consistent with environmental causes, the disparities in socioeconomic status were partly accounted for by children's access to stimulating toys and books, excursions to visit people and places outside the home and parents who talked a lot with them.

The study also found that as a family's income grew, so did children's working memory and planning abilities. Although the evidence is correlational rather than causal, says Farah, genetic differences wouldn't explain why family fortunes and executive function fluctuate in tandem.

Being poor can also affect the minds of adults, according to research by Princeton psychology and public affairs professor Eldar Shafir, PhD, co-author of the 2014 book "Scarcity: The New Science of Having Less and How It Defines Our Lives." (See "The psychology of scarcity" in the February 2014 Monitor on Psychology.)

Scarcity — whether it's a lack of money, time or even food to satisfy a dieter's hunger — can cause "tunneling," or over-focusing on one thing to the detriment of other things, says Shafir. For the poor, focusing on immediate financial crises means there's little "mental bandwidth" left over for other day-to-day tasks, such as overseeing children's homework or taking medicine on time, let alone building an emergency fund or taking other steps toward financial security.

In fact, says Shafir, poverty can actually impede cognitive functioning. In a paper in Science , he and co-authors studied Indian sugarcane farmers and found that they scored the equivalent of 10 IQ points higher in the post-harvest period — when they are relatively rich — than in the pre-harvest period, when they are poor.

Shafir and his colleagues found the same pattern in shoppers at a New Jersey mall. In a series of experiments also described in the Science paper, they asked shoppers with a diverse range of incomes to ponder scenarios designed to trigger their own financial concerns and then undergo cognitive tests. Rich and poor performed similarly when the scenario involved a small sum, such as a $150 car repair bill. But when the scenario involved high costs, such as a $1,500 repair bill, the poor performed significantly worse.

These findings upend the conventional wisdom about who the poor are, says Shafir. "A very common view is that the poor are poor because they're less capable," he says. "Our data suggest it's exactly the opposite: It's poverty that makes them less capable."

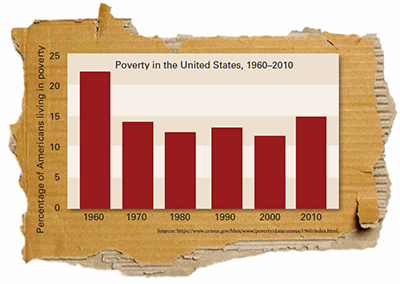

Poverty in the United States, 1960–2010 (Sources: https://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/data/census/1960/index.html)

A large body of evidence is now showing that socioeconomic status is also related to poor physical health, in part via the pathway of stress, says Nancy E. Adler, PhD, who directs the Center for Health and Community at the University of California San Francisco's School of Medicine.

"People lower on the socioeconomic hierarchy are exposed to many more stressful events, have fewer resources for coping with those events and are much more in a state of chronic stress," explains Adler.

That stress-induced wear on the body can shorten telomeres, the caps at the tips of chromosomes that help ensure cell integrity, says Adler. "If telomeres shorten below a critical level, it's a good indicator of cell aging and predicts the onset of many diseases and lower longevity."

Of course, says Adler, there are ways to manage stress. One effective strategy is physical exercise, which appears to buffer the effects of stress. "But people with lower socioeconomic status usually have less time and [fewer] resources to engage in exercise," she says.

In a 2013 paper in Brain, Behavior and Immunity , Adler and co-authors uncovered another potential buffer: education. By comparing educational attainment and telomere length in almost 2,600 older adults, the researchers found significantly shorter telomeres in people with only a high school education. A post-high school education was especially beneficial for African-Americans.

"What we've been learning over the last couple of decades of research is the high cost in health and shorter life of having less education and lower income," says Adler. "What the data linking socioeconomic status and telomere length suggest is how important it is to engage in social policies that will increase education and boost income."

How people living in poverty view the stressors they face can also help, according to research by Edith Chen, PhD, a psychology professor at Northwestern University.

Chen points to a strategy known as "shift and persist," in which low-income young people reframe the stressors they face to seem more benign while continuing to hold on to hopes of a better future. A child might accept stress for what it is while holding on to optimism about the future, for example.

"The shifting part is adjusting yourself to the stressor rather than trying to change the stressor or make it go away," says Chen. "Shifting could be construed as an acceptance of fate, but the persistence part is the idea of still working toward future goals — not just giving up and accepting everything that comes one's way."

Among adolescents of lower socioeconomic status, the shift-and-persist approach appears to reduce the risk of asthma-related problems, obesity and other health issues, Chen has found. In a 2013 paper in Child Development , for example, she and colleagues found that young people who used the strategy most had lower levels of interleukin-6, a marker of inflammation that can lead to cardiovascular disease. The protective effect didn't show up in adolescents with higher socioeconomic status, who have other resources for coping with stressors.

Parental income doesn't just have an impact on young children. Parents' financial circumstances continue to affect children even as they move into early adulthood, says Mindi N. Thompson, PhD, an associate professor of counseling psychology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

In a qualitative study published in 2013 in the Journal of Counseling Psychology , Thompson and colleagues found that undergraduates with an unemployed parent or caregiver reported financial struggles, stigma, difficulty concentrating and a sense of having to grow up faster than peers. Some, however, credited the experience with inspiring them to do what it takes to achieve security in their own careers.

Classism, often combined with racism, can undermine that sense of hope, however.

In a 2014 paper in the Journal of Career Assessment , Thompson and co-authors found that experiencing classism lowered "work hope" — the belief that one will be successful in a future career — in undergraduates of varying socioeconomic backgrounds from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups who attended a predominantly white school.

For Thompson, the findings suggest the need for faculty, staff and administrators in higher education to discuss openly what's often left unsaid — social class. Even one-on-one among friends, she points out, it's still taboo to ask or reveal how much money one makes. While educators often shy away from acknowledging class differences, she says, it's important that they acknowledge that classism exists in students' lives and may affect their ability to study effectively. "If we continue to ignore it, we're doing a disservice to students, especially as campuses become increasingly diverse," she says.

Educators can also help students from lower socioeconomic status backgrounds by providing access to mentors and training in such skills as writing or public speaking that can help them in jobs or in college, says Thompson.

Psychologist Matthew Diemer, PhD, an associate professor in the University of Michigan's College of Education, is investigating how "critical consciousness" can spur young people to work for change.

Borrowed from Brazilian educator Paulo Freire, the concept as developed in Diemer's work involves people critically reflecting on how inequitable treatment, exclusion from societal institutions and limited access to resources have contributed to one's social standing, feeling motivated to effect change in the world and taking action to create a more just world through civic or political engagement.

Diemer's earlier work indicated that critical consciousness can have an impact on the lives of poor adolescents of color. In a 2009 article in the Counseling Psychologist , he found that the poor youth of color who had more critical consciousness in 10th and 12th grades went on to attain higher-paying, higher-status occupations in adulthood than other adolescents — even after controlling for academic achievement.

"Teachers often redirect students away from conversations about things being unequal or unfair," says Diemer, explaining that teachers may worry that talking about such subjects may be discouraging and believe that students should just work hard and hope for the best. "But it seems like critical consciousness provides some armor against marginalization and oppression."

Now Diemer is investigating parents' role in fostering young poor people's political activism. In a 2012 paper in the American Journal of Community Psychology , for example, Diemer found that parents can play a key role in socializing their children's political participation. In this longitudinal study, Diemer found that children of parents who discussed current events with them were more committed to fight for social change in the future. For Latino and Asian-American young people, such conversations with parents predicted whether they would vote or not once they became eligible.

The development of critical consciousness can be impeded by psychological factors, however, says Erin B. Godfrey, PhD, an assistant professor of applied psychology at New York University. Godfrey has found that rather than being one end of a continuum, critical consciousness can co-exist with a belief in the fairness of the system and equality of opportunity — beliefs that give people hope and make them feel better about their own economic situation.

In a qualitative study of 19 low-income women published this year in Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology , Godfrey and psychologist Sharon Wolf, PhD, found that almost all of the participants attributed poverty to character flaws, lack of hard work and other individual factors. Fewer than half cited structural explanations, and when they did, it was almost always in tandem with individual explanations. "People were really relying on these myths about society — that you can get ahead if you just try hard enough," says Godfrey.

While interventions often focus on helping people in poverty develop critical consciousness, says Godfrey, it's important to take into account the motivations people have to justify the current system when developing such programs.

"People hold system-justifying beliefs for a reason," says Godfrey, explaining that it can be very demoralizing to believe that structural factors can impede your success even if you try hard. "We should incorporate this into how we try to help people develop critical consciousness so that we can still give them a sense of efficacy and hope."

Ceballo is exploring another possible buffer against the effects of poverty among Latino families: familismo — a Latino cultural emphasis on family and prioritization of family needs and relationships.

In a 2013 paper in Social Development , Ceballo and Traci M. Kennedy, PhD, found that adolescents' endorsement of familismo was associated with lower levels of exposure to violence — a common occurrence in the lives of many poor people. Plus, youth whose families espouse familismo also had fewer depressive symptoms if they were exposed to violence.

Family can also help boost academic achievement among low-income Latino students. In a 2014 paper in Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology , Ceballo and her co-authors found that three types of parental involvement boosted academic outcomes in low-income Latino adolescents: school-based involvement, parents' discussions with their children about the value of school, and the notion of children doing well academically as a gift to honor parental hard work and sacrifice.

Teachers, says Ceballo, may judge parents' commitment to their children's education by noting whether or not they attend parent/teacher conferences and similar school-based events. But low-income parents may not have the time or resources to attend. Teachers need to understand that if they don't see parents at school, it doesn't mean those parents don't care about their children's education, she says.

"My parents didn't feel comfortable going to my rich private school, couldn't speak to my teachers and couldn't help me with my homework, but they still did a tremendous amount for me," says Ceballo. "They said, ‘We'll do whatever we can to support your education.'"